Rethinking wound healing: from classical readouts to emerging ways of studying tissue repair

Every day, our skin quietly repairs itself after injury, a process that relies on a complex regenerative program. In this blog, we explore what drives effective wound repair, why some wounds fail to heal, and what it takes to translate laboratory insights into meaningful clinical outcomes.

Wound healing: biological complexity & translational challenges

Wound healing is a multi-phase, multi-cellular process involving coordinated interactions between epithelial cells, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and immune cells. Successful repair requires spatially and temporally regulated cellular and molecular events. Disruption of these processes can result in delayed or non-healing wounds.

Despite extensive research, translation from preclinical models to clinical outcomes remains limited. The challenge arises primarily from the complexity of the biological system and limitations of experimental models, rather than a lack of understanding of the underlying biology.

Acute wound healing: the reference model

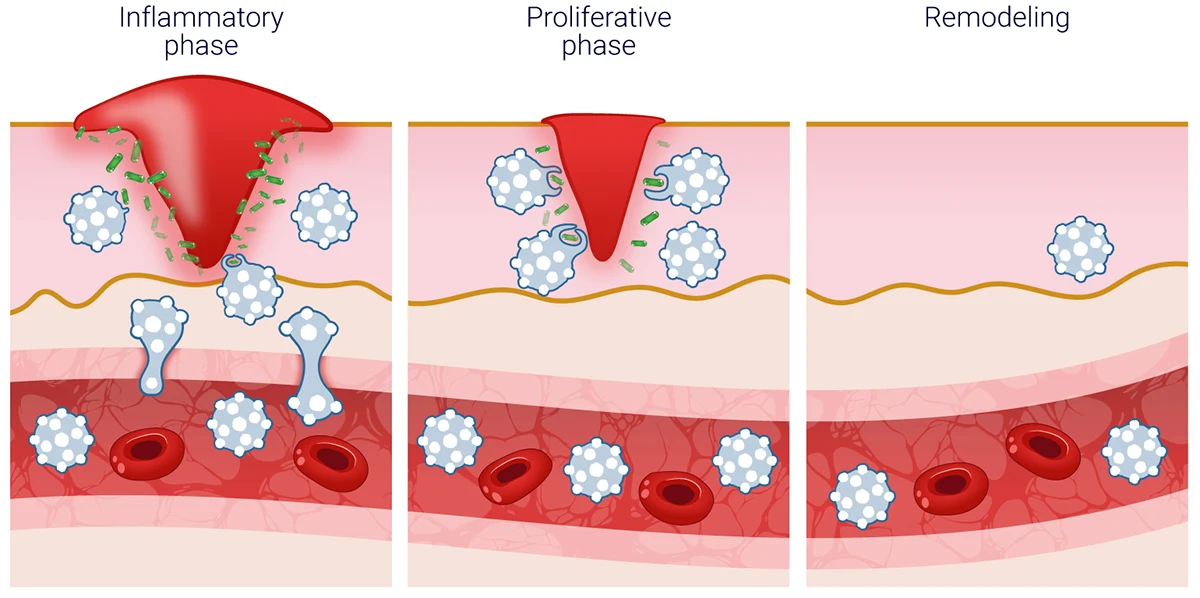

Acute wounds provide a reference state for studying tissue repair. Healing progresses through four interconnected phases:

- Hemostasis: Immediately after injury, blood clotting prevents excessive bleeding and creates a provisional matrix. Platelets release growth factors and cytokines that initiate downstream responses.

- Inflammation: Innate immune cells (primarily neutrophils and macrophages) are recruited to the wound site. They clear debris and pathogens while shaping the inflammatory environment that guides repair.

- Proliferation: Keratinocytes migrate to re-epithelialize the wound surface. Fibroblasts proliferate and deposit extracellular matrix (ECM), while endothelial cells drive angiogenesis to restore perfusion.

- Remodeling: The newly formed tissue is gradually reorganized. Collagen is remodeled, cellularity decreases, and tensile strength improves as the tissue matures.

In healthy wounds, these events are precisely regulated in time and space. Controlled resolution of inflammation is essential for progression to tissue repair, whereas sustained immune activation is commonly associated with impaired healing and chronic wounds.

Classic readouts to study wound healing

Historically, wound healing has been evaluated using histological, molecular, and functional readouts.

Structural and histological assessments

- Re-epithelialization rate

- Granulation tissue formation

- Collagen deposition and organization, visualized with Masson’s trichrome or Sirius red staining

These measures provide information on tissue architecture and remodeling (Singer & Clark, 1999; Gurtner et al., 2008).

Cellular & molecular readouts

- Inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6)

- Growth factors (VEGF, TGF-β)

- Proliferation markers (e.g., Ki-67)

These analyses characterize immune activity, cell proliferation, and growth factor signaling during repair (Eming et al., 2007; Barrientos et al., 2008).

Functional readouts

- Wound closure rate

- Tensile strength during late remodeling

Functional endpoints provide a measure of the overall repair outcome (Gurtner et al., 2008).

Limitations

Classical approaches are predominantly endpoint-based, limiting temporal resolution. They provide limited insight into immune cell heterogeneity and do not fully capture dynamic cellular interactions. Consequently, mechanistic understanding is often incomplete.

Emerging ways to study wound healing

Recent methodological developments provide high-resolution, human-relevant, and dynamic insights into tissue repair.

Multi-omics & spatial analyses

- Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals cell states rather than broad cell types, uncovering transitional and rare populations involved in repair (Joost et al., 2018; Guerrero-Juarez et al., 2019).

- Spatial transcriptomics connects gene expression to tissue architecture, linking structure and function within the wound bed (Phan et al., 2020).

Immune-aware readouts

- Detailed phenotyping of macrophages and T-cell subsets demonstrates their role in modulating fibroblast function, angiogenesis, and epithelial repair (Krzyszczyk et al., 2018; Nosbaum et al., 2016).

- Longitudinal cytokine profiling enables characterization of immune dynamics over the course of repair, rather than isolated measurements (Eming et al., 2017).

These approaches acknowledge that inflammation is not simply “on” or “off,” but continuously evolving.

Dynamic and longitudinal monitoring

Repeated sampling, time-course molecular analyses, and integration of functional and structural data allow reconstruction of temporal healing trajectories. Computational and AI-based methods further enable identification of predictive biomarkers and modeling of repair outcomes (Berezo et al., 2021).

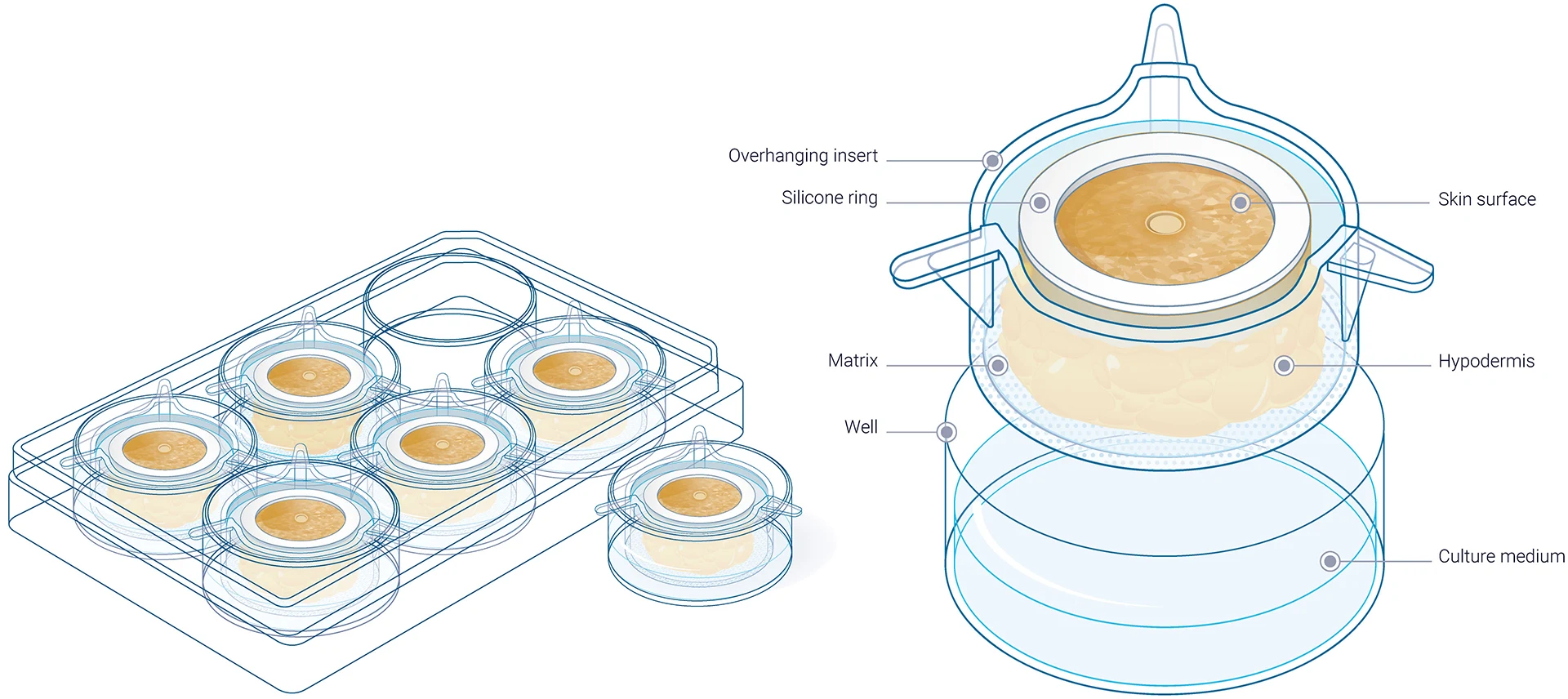

Advanced ex vivo models

A key driver of recent progress in wound healing research is the increasing use of human-relevant tissue models. Among these, human ex vivo skin explants offer distinct advantages by preserving tissue architecture, extracellular matrix, and resident immune populations, features that are largely absent from simplified in vitro models.

Unlike reconstructed skin or monocellular cultures, ex vivo human skin models enable investigation of wound healing within an intact tissue environment, maintaining physiologically relevant interactions between epidermal, stromal, vascular, and immune compartments.

Within this framework, WoundSkin® is an immunocompetent ex vivo human skin model developed specifically for the study of wound healing and tissue repair. The model preserves:

- Natural skin architecture

- Functional resident immune cells

- Interactions between fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and endothelial cells

In addition, WoundSkin® supports longitudinal analysis, enabling researchers to follow healing over time rather than relying on single endpoints. A multi-donor approach further captures inter-individual variability, which is a critical factor when translating findings to the clinic.

Integration with computational and AI tools

The growing volume and complexity of data are driving the use of computational modeling and AI to:

- Identify predictive biomarkers

- Model healing trajectories

- Link early molecular events to long-term outcomes

From observation to prediction: the next step

Descriptive data alone is no longer sufficient. The field is moving toward mechanistic, predictive models that reflect human biology and immune complexity.

To achieve this, researchers need:

- Human-relevant systems

- Immune-aware experimental designs

- Longitudinal, multi-dimensional readouts

These tools are particularly critical when studying wounds that fail to heal, where dysregulated inflammation, impaired immune resolution, and altered tissue dynamics drive chronic pathology.

Conclusion

Wound healing research is shifting from static observation to dynamic, immune-aware, and human-relevant investigation. By combining advanced biological readouts with next-generation ex vivo models like WoundSkin®, the field is moving closer to understanding not just how wounds heal but why they sometimes don’t.

References

Cutaneous wound healing.

Singer, A. J., & Clark, R. A. (1999).

The New England journal of medicine, 341(10), 738–746.

Wound repair and regeneration.

Gurtner, G. C., Werner, S., Barrandon, Y., & Longaker, M. T. (2008).

Nature, 453(7193), 314–321.

Inflammation in wound repair: molecular and cellular mechanisms.

Eming, S. A., Krieg, T., & Davidson, J. M. (2007).

The Journal of investigative dermatology, 127(3), 514–525.

Growth factors and cytokines in wound healing.

Barrientos, S., Stojadinovic, O., Golinko, M. S., Brem, H., & Tomic-Canic, M. (2008).

Wound repair and regeneration : official publication of the Wound Healing Society [and] the European Tissue Repair Society, 16(5), 585–601.

Single-Cell Transcriptomics of Traced Epidermal and Hair Follicle Stem Cells Reveals Rapid Adaptations during Wound Healing.

Joost, S., Jacob, T., Sun, X., Annusver, K., La Manno, G., Sur, I., & Kasper, M. (2018).

Cell reports, 25(3), 585–597.e7.

Single-cell analysis reveals fibroblast heterogeneity and myeloid-derived adipocyte progenitors in murine skin wounds.

Guerrero-Juarez, C. F., Dedhia, P. H., Jin, S., Ruiz-Vega, R., Ma, D., Liu, Y., Yamaga, K., Shestova, O., Gay, D. L., Yang, Z., Kessenbrock, K., Nie, Q., Pear, W. S., Cotsarelis, G., & Plikus, M. V. (2019).

Nature communications, 10(1), 650.

Lef1 expression in fibroblasts maintains developmental potential in adult skin to regenerate wounds.

Phan, Q. M., Fine, G. M., Salz, L., Herrera, G. G., Wildman, B., Driskell, I. M., & Driskell, R. R. (2020).

eLife, 9, e60066.

The Role of Macrophages in Acute and Chronic Wound Healing and Interventions to Promote Pro-wound Healing Phenotypes.

Krzyszczyk, P., Schloss, R., Palmer, A., & Berthiaume, F. (2018).

Frontiers in physiology, 9, 419.

Cutting Edge: Regulatory T Cells Facilitate Cutaneous Wound Healing.

Nosbaum, A., Prevel, N., Truong, H. A., Mehta, P., Ettinger, M., Scharschmidt, T. C., Ali, N. H., Pauli, M. L., Abbas, A. K., & Rosenblum, M. D. (2016).

Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950), 196(5), 2010–2014.

Inflammation and metabolism in tissue repair and regeneration.

Eming, S. A., Wynn, T. A., & Martin, P. (2017).

Science (New York, N.Y.), 356(6342), 1026–1030.

Predicting Chronic Wound Healing Time Using Machine Learning.

Berezo M, Budman J, Deutscher D, Hess CT, Smith K, Hayes D.

Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2022;11(6):281-296.

Comments are closed.